VATICAN CITY – It’s being called the Sistine Chapel of calligraphy. The Saint John’s Bible will be the first handwritten and illuminated Bible penned with ancient methods since the invention of the printing press, according to its creators.

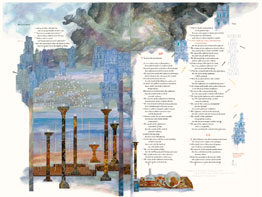

This Biblical work of art will contain some 160 illuminations woven into text covering 1,100 pages of calfskin vellum sheets.

A team of scribes led by a master calligrapher, Donald Jackson, has spent the last 10 years silently scratching out Biblical verses with turkey, goose and swan quills dipped in handmade inks. They and other artists also use hand-ground pigments and gold and silver leaf to illustrate and add contrasting colors to the texts.

The huge manuscripts will be bound into seven volumes that measure two feet tall and, when open, three feet wide. Five of those volumes are now complete.

U.S. Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, retired archbishop of Washington and president of the U.S.-based Papal Foundation, called the project “one of those special moments in the life of biblical art.”

He was part of a delegation that met with Pope Benedict XVI April 4 to present him with a high-quality, rare reproduction of the first volume of The Saint John’s Bible.

The pope, a great lover of books and sacred Scripture, was awed – his eyes glistening “with great joy” as he said, “‘This is a great work of art,’“ the cardinal said at a press conference soon after.

Jackson said the pope told him, “This is a work for eternity,” to which the artist said he replied, “It certainly feels like it sometimes.”

At the press conference, Jackson asked the question most people might pose: “Why do it? I mean it’s a crazy idea to turn the clock back 500 years” in this day and age of computers and laser-jet printers.

But he said the tools of the old medieval scribes “enable you to write the words of God from the heart.”

And by creating such a hefty, richly illustrated book whose pages look and even feel special, the reader is being told to “slow down, set this volume down carefully” and meditate over each and every word; it is not something to flip through casually, Jackson said.

In fact, one of the aims of this project, commissioned in 1998 by the Benedictine monks of St. John’s Abbey and University in Collegeville, Minn., is to glorify the word of God.

Jackson said modern technology has “solved the problem of dissemination. Every hotel room has a choice of one, if not two, Bibles in the nightstand.”

But often mass-produced Bibles are printed with small, cramped type on cheap “onion-skin” thin paper and put what should be thought-provoking passages of God’s word “in a straitjacket,” he said.

The Bible needs to also reach out to the human senses, not just the intellect, he said.

The Saint John’s Bible, with its large pages and creatively arranged text, “invites one to linger over phrases, words and even letters” and “presents the word of God as something special,” said one of the project’s many press releases.

Even the artwork, which ranges from Byzantine icons to modern styles and botanically correct renderings of insects and plants, is meant to invite the reader toward greater reflection.

Jackson said he and his scribes have had “to let go of modern conceptions of perfection” and of creating a flawlessly copied text. They cannot, after all, hit the delete button or use correction fluid to cover up mistakes.

Small errors can be scraped away with a sharp knife-edge, he said, but a more common “occupational hazard” of accidentally omitting a line is not so simply corrected.

But with the help of their artists they have been able to turn “what was a disaster into something charming,” Jackson said.

For example, an artist has drawn a small bird grasping a rope that holds a banner upon which is written the missing verse. The bird is pointing its beak to where the line should go while appearing to be hoisting the forgotten line back where it belongs. A chubby bumblebee does the same thing in another volume, only she is using a pulley system copied from one of Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbooks.

A limited number of high-quality, full-size, fine art reproductions have been produced for special benefactors. The pope’s rare copy was a gift from St. John’s University and Abbey purchased on behalf of a trustee from the U.S.-based Papal Foundation.

The gift and its publicity come the same year the world Synod of Bishops is gathering at the Vatican this fall to discuss the importance of sacred Scripture.

Synod leaders have said they hope the meeting can address what is seen as a lack of appreciation and understanding of the Bible among Catholics.

Pope Benedict has said the Bible “requires special veneration and obedience” by all Christians, and he said he hoped the synod process would help Catholics “rediscover the importance of the Word of God in the life of every Christian.”

But while most people will not be able to afford the minimum $115,000 price tag of the special-edition sets, more affordable smaller, hardbound copies are for sale through www.litpress.org, or by clicking “gift shop” at: www.saintjohnsbible.org.

The Saint John’s Bible uses the New Revised Standard Version and, when completed in 2009, will include volumes that include Gospels and Acts, Psalms, Pentateuch, Historical Books, Prophets, Wisdom Literature, and Letters and Revelation.

The finished original manuscript crafted by Jackson and his team will reside at a special museum on the St. John’s University campus.

It is not the first time Jackson brought a piece of his “Sistine Chapel” to the Vatican; he also gave Pope John Paul II a limited-edition prototype of the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles at the Vatican in 2004.

While unique, these papal copies of The Saint John’s Bible are not the only rare specimens of sacred Scripture to grace the Vatican’s bookshelves.

The Vatican Library has a fourth-century Codex B manuscript – a complete text of the Bible in Greek – as well as two copies of the Gutenberg Bible. This Bible was one of the first books printed by the movable type process invented by Johann Gutenberg in 1455, and only about 60 copies remain.