LIMA, Peru – Around the corner from the health center in Quiquijana, a village in the southern Peruvian Andes, a scenic wall painting depicting a woman in colorful local dress announces the location of the “Mama Wasi,” or “mother’s house.”

Inside a traditional colonial house built around a cobbled courtyard, pregnant women, some of whom have walked for six hours or more to reach the village, live in simple rooms while they await their babies’ birth. They tend older children, hang laundry in the sun and cook over traditional wood stoves like the ones in their distant homes.

Women can stay at the house for days or weeks before delivery, if necessary. When labor begins, they are attended by Quechua-speaking nurses and obstetricians and can choose to give birth kneeling or squatting, the traditional birthing position in that area, with their husbands or other relatives nearby to provide support.

The Quiquijana health center used to have a conventional delivery room and a non-Quechua-speaking staff. The changes, which make the center more welcoming to Andean women, mark an effort by Peruvian health authorities to reduce Peru’s high maternal mortality rate.

Maternal mortality in Quiquijana has dropped to zero, but the national rate is still high – 185 mothers die per 100,000 live births, according to the Health Ministry, and 240 per 100,000 live births according to the United Nations. By 2015, Peru might not hit its target of cutting it to 120 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

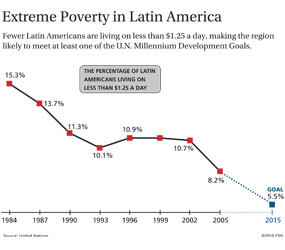

The target is one of the Millennium Development Goals, objectives set by the world’s nations in 2000 to reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of the world’s poorest people. With five years to go, progress is notable, but countries still fall short in some areas.

Peru’s maternal mortality rate – which has dropped by half in rural areas, but is still far higher than that of countries like Uruguay, with 20, or Costa Rica, with 30 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births – highlights a problem the overall statistics conceal. Even if countries hit their targets, poverty rates may remain high among indigenous people, women, children and rural residents.

“If you look at the average numbers, it looks like Latin America is doing better,” especially compared to sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, said Aldo Caliari of the Jesuit-run Center of Concern in Washington.

But he said when a view of the Millennium Development Goals through other lenses, “such as the situation of minorities and inequality,” shows the gap between the wealthiest and poorest inhabitants is growing, “some of us find it difficult to call that progress.”

At a Sept. 20-22 summit on the Millennium Development Goals, delegates from around the world discussed progress toward the targets of eliminating extreme poverty and hunger, ensuring primary education for all, empowering women, reducing child mortality, improving maternal health, combating AIDS and other diseases, ensuring environmental sustainability and working together for development.

The delegates noted, however, that the world is falling short of the targets. The recent global economic crisis slowed or reversed progress in some areas, but Caliari, who attended the U.N. summit, said the problems go beyond a lack of money.

“What it takes is leadership, and I don’t see on the world stage that we have the kind of leadership that is required,” he said.

The percentage of Latin Americans living on less than $1.25 a day dropped from 11 percent in 1990 to 8 percent in 2005, making the region likely to meet its goal of 5.5 percent by 2015. High demand for export commodities like soy, copper and other metals has buffered many Latin American nations from the worst of the international crisis.

But environmental problems associated with resource extraction have spurred conflicts in the region, and U.N. figures show the region’s high deforestation rate has barely budged, dropping only from 52 percent to 48 percent since 1990. And although the region’s economy grew in the past decade, there was little change in overall employment rates.

The number of people suffering from hunger and the percentage of malnourished children has decreased more in Latin America than in other regions of the world, but children in rural areas are still more than twice as likely to suffer from malnutrition than their urban counterparts. The urban-rural gap also holds true for primary education and access to water and sanitation.

Some millennium goals also show a gender gap. In Latin America, although girls outnumber boys in high school and post-secondary education, women hold only one-third of top-level jobs. In places such as Panama, Venezuela, urban Brazil and Mexico, more than half of all women in non-farm jobs work in the informal economy, with no benefits or security. The figure rises to more than 70 percent in cities in Peru and Ecuador.

The region is close to its target of cutting child mortality by two-thirds from the 1990 rate of 52 percent, but farther from the goal of reducing maternal deaths by three-quarters. The region also has the world’s second-highest rate of teenage pregnancy, trailing only sub-Saharan Africa.

A major obstacle to more equitable distribution of the world’s resources, leading to elimination of poverty, is an overemphasis on consumption as the motor of economic growth, Caliari said. At the September summit, the prime minister of Bhutan suggested gauging economic success by “gross national happiness” instead of “gross national product,” he said.

Catholics must take global poverty and inequality seriously because of their Christian commitment to solidarity and the common good, and economic issues ties the world’s people together, Caliari said.

“We need a dramatic rethinking of growth and consumption,” he said. “The question that’s at stake is, ‘What matters ultimately to us?’ Are we producing growth for the sake of growth, or are we producing an economy that can meet the needs of people (who have) a sense of identity (and) are producing something for society?”