By Rafael Alvarez

Special to the Review

Sister Mary Roseanne Spurrier, 96 and with more than six decades of religious life to her credit, was one of eight School Sisters of Notre Dame – all in full habits – teaching at St. Jerome’s School in Southwest Baltimore on the Friday before Thanksgiving, 1963.

An Irvington native from the 300 block of Augusta Avenue, Sister Roseanne taught a fourth-grade class with more than 50 children. Her students, many of them she remembers as having hard lives, were at recess when a fire broke out Nov. 22.

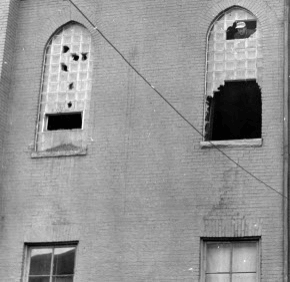

For a couple hours, the four-alarm fire at the corner of Scott and Hamburg streets was the biggest news in Baltimore, but it became an afterthought when word came that John F. Kennedy, the first and only Catholic president of the United States, had been assassinated that afternoon in Dallas.

Sister Judith Schaum, not much more than a novice at the time and now 74, was also teaching at St. Jerome’s that eventful morn.

“It was a raw, damp November day and it was lunchtime,” she said, noting that a neighborhood kid in a feud with a St. Jerome’s student had snuck into the auditorium of the Pigtown parochial school and set fire to a set of drapes.

A suspicious fire had been discovered the day before in a library desk but was extinguished without serious damage. This one was different.

“I was having lunch in the convent and most of the kids were out in the yard,” said Sister Schaum, currently the regional director of Mission Effectiveness for the 180-year-old order.

“Sister Elizabeth (Mary Foster) was on playground duty and came in to tell us there was smoke coming out of the second floor of the building. We used to have girls selling candy in the school at lunch time and I ran over to the school to make sure they were all out.

“The kids all got in their lines so we could take count and make sure everyone was there.”

“The teachers went back after the fire was out and stood in the yard to look; they (firefighters) had to rip through the roof,” said Sister Judith. “We were standing there looking at the building when we got word (from Dallas). The fire was so personal and then this. I thought, ‘Oh Lord, what else can go wrong?’

“It was a very dark day in many ways.”

The school principal and superior of the convent that year was Sister Oswin Simon. She is deceased along with Sister Concetta Imperato, Sister Agnes Leahy and Sister Richard Marie Cashen.

The other surviving religious from the 1963-1964 St. Jerome’s teaching staff are former fifth-grade teacher Sister Elizabeth and Sister Mary Aloysius Norman, who on the day of the assassination was a second-grade teacher celebrating her 24th birthday.

“The sisters were all very upset,” Sister Roseanne said, “especially Sister Concetta, the music teacher.”

St. Jerome’s School closed in 1973. The historic parish, founded in 1887, is now the home of Transfiguration Catholic Community.

“There had been a tremendous (public) concern that a Catholic president would get interference from the Vatican,” Sister Judith said “That concern was misplaced. By the time (of JFK’s assassination) that phobia was no longer.”

And then Sister Judith posited the unanswerable – something ascribed to Lincoln and Dr. King and the Kennedy brothers that has vexed historians and everyday people alike for the past 50 years: “Had he only been able to finish …”

Asked if she was especially fond of JFK, Sister Roseanne spoke for the sisters on duty that day, saying, “We all were … we were all very proud of him.”

Like most every institution across the country, St. Jerome’s School was closed Monday, Nov. 25, the day of the president’s funeral at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington.

Instead of classes, St. Jerome celebrated requiem Mass that same day for John Fitzgerald Kennedy, age 46.

“We watched it all,” said Sister Schaum, “from beginning to end.”

Source material

This article was inspired by the first chapter of a new book by Michael Olesker, “Front Stoops in the Fifties: Baltimore Legends Come of Age” (Johns Hopkins University Press). In a chapter titled “The Day the Fifties Ended,” Olesker gives a full account of Nov. 23, 1963 in Baltimore – from the fire at St. Jerome to young radio reporter Frank Luber trying to cover everything at once on that miserable day.

Also see: