Jan. 21, 2019

As our country this month commemorates the birth of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., one of our nation’s most revered champions of racial justice, we cannot help but question whether his dream of racial unity will ever be attained. Even as we Americans celebrate his inspiring example, we feel the shame of witnessing public demonstrations of racial and ethnic violence and hatred such as we have not seen in decades. Whether racism manifests itself in these blatant offenses against the dignity and humanity of people of color, or more subtly in the systemic racial inequities that persist in our current society — in the criminal justice system, in employment, education, housing, healthcare, and political enfranchisement — the national conversation confirms that there is still a great deal of work to be done.

While it has only been a year since I wrote a pastoral statement on Dr. King’s principles of nonviolence, there is a continued urgency to address the issue of racism, especially given the ongoing rise of horrifying incidents of racism, anti-Semitism and intolerance toward newcomers to our country. The urgency has also been highlighted through the recent publication of a national pastoral letter against racism, Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love, in which the U.S. bishops forthrightly recognize racism as a sin: “Racist acts are sinful because they violate justice. They reveal a failure to acknowledge the human dignity of the persons offended, to recognize them as the neighbors Christ calls us to love (Mt 22:39). … Every racist act — every such comment, every joke, every disparaging look as a reaction to the color of skin, ethnicity, or place of origin — is a failure to acknowledge another person as a brother or sister, created in the image of God. In these and in many other such acts, the sin of racism persists in our lives, in our country, and in our world.”

Also within the past year, the Church has been rocked by a crisis of a magnitude many of us never thought possible. The people of God’s faith in the institutional Church, and most especially its leaders, has — rightfully — been shaken to the core. As I have participated in consultations, listening sessions, conversations, and moments of prayer since this crisis first erupted, I have come to realize in a new and clearer way an important truth: wherever the people of God are suffering is where I belong, at their side, listening, sharing compassion, and discerning how the Holy Spirit is calling me to take action.

And so it is with this heart that I wish to turn again to the issue of racism, and to my sisters and brothers who continue to suffer from the effects of this sin — in our Catholic community, in the City of Baltimore, and throughout the territory of the Archdiocese. The earlier pastoral on Dr. King is an important first step in this conversation, but as the rhetoric of intolerance and hatred continues to spiral in our local and national communities, it is clear there is still much more to say, and still much, much more to do.

Recognizing always our need for redemption, we must keep at the foundation of our journey forward the conviction that the best solutions to the sin of racism and the social and political ills that racism engenders will be centered in the teachings of Jesus Christ and led by His Holy Spirit. Again and again, we must take the words of Jesus to heart: “I give you a new commandment: love one another. As I have loved you, so you also should love one another” (Jn 13:34).

As the U.S. bishops declared in their recent statement, “What is needed, and what we are calling for, is a genuine conversion of heart, a conversion that will compel change, and the reform of our institutions and society. Conversion is a long road to travel for the individual. Moving our nation to a full realization of the promise of liberty, equality, and justice for all is even more challenging. However, in Christ we can find the strength and the grace necessary to make that journey.” And so I invite all of the Catholic faithful throughout the Archdiocese of Baltimore to forge ahead on this journey together.

In reflecting on how entrenched the issue of racism appears to be in our American society, we must first take the necessary step of engaging in an honest examination of our own past. While today we witness the effects of racism against many ethnicities and people of color, the historical roots of racism against African-Americans in our country cannot be ignored. We must therefore acknowledge the Church’s historical involvement in a society in which the institution of slavery was deeply embedded. No doubt, in looking back at the history not only of our Church, but also of our nation, one may justly say that racism is the original sin of our country, our state, and our local dioceses, and its deep roots continue to plague us. As we are so painfully aware in the midst of the current crisis in the Church, without acknowledging the sins of the past, we cannot hope to understand and heal the wounds of the present.

In reflecting on how entrenched the issue of racism appears to be in our American society, we must first take the necessary step of engaging in an honest examination of our own past. While today we witness the effects of racism against many ethnicities and people of color, the historical roots of racism against African-Americans in our country cannot be ignored. We must therefore acknowledge the Church’s historical involvement in a society in which the institution of slavery was deeply embedded. No doubt, in looking back at the history not only of our Church, but also of our nation, one may justly say that racism is the original sin of our country, our state, and our local dioceses, and its deep roots continue to plague us. As we are so painfully aware in the midst of the current crisis in the Church, without acknowledging the sins of the past, we cannot hope to understand and heal the wounds of the present.

At the same time, however, the makeup of Maryland’s Catholic community was being transformed by waves of immigrants, themselves victimized by ethnic prejudice and anti-Catholic sentiment. Yet those national parishes of German, Polish, and Italian immigrants, as well as other immigrant congregations of the faithful, were still influenced by the racist tendencies of the general society. As the Church welcomed and supported these European immigrants who today enjoy a remarkable

At the same time, however, the makeup of Maryland’s Catholic community was being transformed by waves of immigrants, themselves victimized by ethnic prejudice and anti-Catholic sentiment. Yet those national parishes of German, Polish, and Italian immigrants, as well as other immigrant congregations of the faithful, were still influenced by the racist tendencies of the general society. As the Church welcomed and supported these European immigrants who today enjoy a remarkable

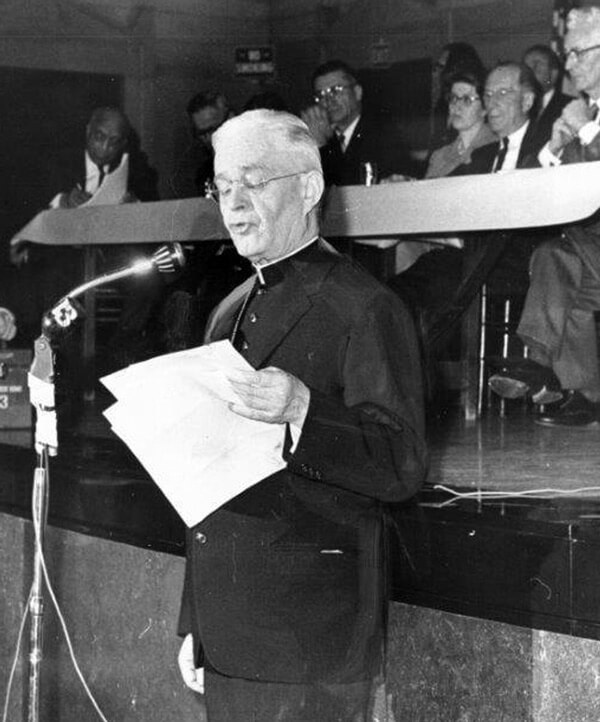

Efforts to more truly embrace the Gospel call began to emerge prior to and during the era of the Civil Rights Movement, which continues today. Decades before the Civil Rights movement blossomed, Church leaders in Maryland, including Baltimore Archbishop Michael Curley1, Cardinal Patrick O’Boyle of the Archdiocese of Washington2, and Bishop Edmond Fitzmaurice3 of the Diocese of Wilmington worked to integrate the Catholic community through a variety of efforts, and desegregated Catholic schools throughout the state, all before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. As Cardinal O’Boyle stated, the bishops “[saw] no reason why a black child was not just as much entitled to a Catholic education as a white child.”

Efforts to more truly embrace the Gospel call began to emerge prior to and during the era of the Civil Rights Movement, which continues today. Decades before the Civil Rights movement blossomed, Church leaders in Maryland, including Baltimore Archbishop Michael Curley1, Cardinal Patrick O’Boyle of the Archdiocese of Washington2, and Bishop Edmond Fitzmaurice3 of the Diocese of Wilmington worked to integrate the Catholic community through a variety of efforts, and desegregated Catholic schools throughout the state, all before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. As Cardinal O’Boyle stated, the bishops “[saw] no reason why a black child was not just as much entitled to a Catholic education as a white child.”  archdiocesan institutions by 1965, and in 1966 established the Archdiocesan Urban Commission charged with addressing discrimination within the Archdiocese. He appointed Charles Tildon, a community activist, public servant, and educator,4 to head the commission, marking the first time a layman had been appointed to a major archdiocesan post. Beyond the boundaries of the Catholic community, Cardinal Shehan sometimes confronted withering criticism for his vocal advocacy for the social justice concerns of African Americans in Baltimore, particularly racial disparities in housing. As many Catholic men and women, including many priests and nuns, participated in the Civil Rights movement over the ensuing years, they joined the many efforts, sacrifices, and achievements fueling the hope that the country was finally “fixed” on policies and programs that would achieve racial justice on a grand scale.

archdiocesan institutions by 1965, and in 1966 established the Archdiocesan Urban Commission charged with addressing discrimination within the Archdiocese. He appointed Charles Tildon, a community activist, public servant, and educator,4 to head the commission, marking the first time a layman had been appointed to a major archdiocesan post. Beyond the boundaries of the Catholic community, Cardinal Shehan sometimes confronted withering criticism for his vocal advocacy for the social justice concerns of African Americans in Baltimore, particularly racial disparities in housing. As many Catholic men and women, including many priests and nuns, participated in the Civil Rights movement over the ensuing years, they joined the many efforts, sacrifices, and achievements fueling the hope that the country was finally “fixed” on policies and programs that would achieve racial justice on a grand scale.

These efforts, encouraging as they may be, cannot by themselves end racial injustice, nor can they be causes of complacency. As the U.S. bishops noted in their pastoral letter:

These efforts, encouraging as they may be, cannot by themselves end racial injustice, nor can they be causes of complacency. As the U.S. bishops noted in their pastoral letter:

As we reflect on the sins of our past, we recognize we are powerless to undo the harm that so many suffered, and that God alone has the power to provide healing for worlds gone by. We can and do pray for those victims of old, for their awful plight; we pray that in the end, God has embraced them with the love and mercy that their fellow Christians all too often withheld from them. In a spirit of gratitude, we also acknowledge the many African-American Catholics today who have carried on the faith of their enslaved ancestors in spite of the wrongs they endured. And so, in a spirit of repentance and prayer, we seek healing as we turn to the redeeming and reconciling love of Jesus with the hope of building a Church that is journeying toward a better future as we work side by side with those who are victims of racism today.

As we reflect on the sins of our past, we recognize we are powerless to undo the harm that so many suffered, and that God alone has the power to provide healing for worlds gone by. We can and do pray for those victims of old, for their awful plight; we pray that in the end, God has embraced them with the love and mercy that their fellow Christians all too often withheld from them. In a spirit of gratitude, we also acknowledge the many African-American Catholics today who have carried on the faith of their enslaved ancestors in spite of the wrongs they endured. And so, in a spirit of repentance and prayer, we seek healing as we turn to the redeeming and reconciling love of Jesus with the hope of building a Church that is journeying toward a better future as we work side by side with those who are victims of racism today.