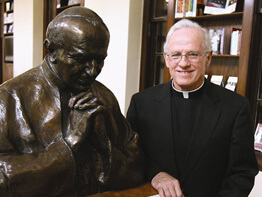

By his own admission, Father Robert F. Leavitt, S.S., was an unusual choice to lead St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Roland Park.

When the Connecticut native was named the 14th president and first president-rector in 1980, he was only 37. He didn’t have any administrative experience and had only recently become a member of the Sulpicians – the order of teaching priests who have run America’s first Catholic seminary since its founding in 1791.

Father Leavitt’s mother and friends advised against taking the post at his alma mater, fearing the intellectual young man was better suited for the classroom than the boardroom.

What made it all the more challenging was that many believed the seminary had reached a nadir in its proud history. Awash in red ink and suffering from declining enrollment, St. Mary’s seemed without direction. Six different leaders within the previous 17 years had found few successes in stabilizing the venerable institution.

Yet Father Leavitt’s superiors saw something promising in the popular professor they had earlier asked to join the seminary’s faculty after he graduated and was ordained in 1968.

He was unquestionably earnest and bright – a gifted homilist and aspiring author who had completed a doctoral dissertation on the thought of Paul Ricoeur, a French philosopher with whom Father Leavitt studied personally in Chicago and Paris.

But there was one other attractive quality in this shooting star that made him the ideal man for the job: he showed a willingness to embrace the Second Vatican Council without throwing away centuries of church tradition.

Twenty seven years later, Father Leavitt is preparing to step down as president-rector. The longest-serving president or rector in the seminary’s history, he will leave St. Mary’s in a much different condition than he found it.

Father Leavitt’s fingerprints are everywhere – from new buildings and programs to an endowment whose value has increased more than 15 times over during his tenure.

Sitting in a meeting room at St. Mary’s with a large painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus perched over his shoulder, Father Leavitt told The Catholic Review his life has been profoundly shaped by his experiences at St. Mary’s.

He expressed intense pride in the quality of the future priests that are formed in his seminary. And the 64-year-old clergyman recounted the joys and struggles of being the leader of a historic institution as it emerged from exciting but turbulent times.

‘Never wanted to be a priest’

Father Leavitt never set out to become a priest.

The only reason the former altar boy attended St. Thomas Seminary high school in the Hartford, Conn. archdiocese was that it was the only place he could get a private, Catholic secondary school education. The school enrolled students like Father Leavitt with one caveat:

“The priest told my mother that I just had to say I’m not opposed to becoming a priest if God calls me,” Father Leavitt remembered with a laugh. “You can’t put up resistance.”

But the more he saw of the collared clerics who ran the school, the more he wanted to be like them. These were men who could speak Greek and Latin. They knew all about philosophy, classical literature, physics and chemistry. What’s more, they were athletes. Father Leavitt himself was a strong-armed pitcher who would later display his talents as a golfer in Charm City.

Determined to become a well-rounded and spiritual man like those he met in high school, Father Leavitt left for St. Mary’s carrying a black suit on a Trailways bus bound for Baltimore in the early 1960s.

The young man’s first two years at seminary were at the old St. Mary’s on Paca Street in downtown Baltimore.

Back then, the seminary was housed in a five-story brick building whose tall walls shielded students from the seedy neighborhood that surrounded it.

The place was unlike anything Father Leavitt had expected, with students required to fetch their water for shaving from a common bathroom.

“The whole intellectual atmosphere belied the building,” said Father Leavitt, a white-haired man who smiled at the memory of quainter times.

“The building was walled off,” he said, “but ideas are coming in from everywhere.”

Father Leavitt said he was deeply impressed by the Sulpicians who taught at the seminary.

“These guys were reading the latest philosophers and finding something there that was worth listening to,” he said. “They were asking ancient and perennially valid questions in new ways.”

The young seminarian’s enthusiasm grew when he began studying two years later at St. Mary’s Roland Park campus. It was right during the Second Vatican Council and some of his professors had attended the council and talked to their students about encounters with famous theologians like Father Karl Rahner, S.J.

“The council had so much energy, the church couldn’t contain it afterwards,” said Father Leavitt, his New England accent only slightly diluted by his decades in Baltimore.

“It was almost like you had this incredible experience of the universal church with every great idea that’s been worked on for a hundred years and the ideas are like the fresh wine in the old wine skins,” he said.

After Father Leavitt was ordained a priest for Hartford and began serving on St. Mary’s faculty with the permission of his bishop, he said one of his major thrusts was harnessing the energy unleashed by the council.

“That’s really a large part of what I feel I’ve tried to achieve – to bring the energy of the council into contact with more of the tradition of the church so that the two don’t pull apart,” he said.

Enacting a vision

After a dozen years serving on St. Mary’s faculty, Father Leavitt was perfectly content with his priestly ministry. From time to time his superiors at the seminary asked him to become a Sulpician, but his bishop would never let him.

The whole time he was on the faculty, he served under one-year contracts –

never knowing when his bishop might call him home.

Then, in the middle of a tennis match outside St. Mary’s, Father Leavitt received word that the Sulpician provincial leader wanted to see him. Father Leavitt met with the Sulpician official and was stunned when he was asked to become a candidate for president-rector of St. Mary’s – a new position that joined the two previously independent posts under a single leader. The provincial promised to make arrangements with Father Leavitt’s bishop so he could become a Sulpician, which happened quickly. He got the job.

The early years weren’t easy. While the spirit of the times had promoted free-wheeling thinking, it led to interminable experimentation at the seminary and an exaggerated sense of collaboration.

The faculty didn’t like the new president’s decision to form a senior administrative team that would shape the overall direction of the seminary.

“The faculty was used to making every decision,” said Father Leavitt, noting that it got to the point of professors even deciding what color paint went on the walls.

Every year, the seminary program was being reinvented on some new “experimental” model, he remembered.

Father Leavitt’s new administrative structure enabled him to “cut through this very thick, tangled web of faculty and collegial interests to get the institution moving forward,” he said.

The president-rector said one of his best decisions was working with a lay board that introduced him to the corporate and philanthropic community. He pitched his vision for the seminary to prominent leaders who supported it with their wallets. He wanted to shape priests who were intellectually disciplined, socially well formed, grounded in prayer and spirituality and able to reach out pastorally.

Within two years, $2 million was raised. A capital campaign was launched in 1986 that raised $10 million. More than $7 million would later be raised for the Center for Continuing Formation and $9 million for the library. Father Leavitt also worked to support the Ecumenical Institute of Theology and he endowed five seminary faculty chairs for $7.5 million.

His latest gem is the Pope John Paul II Reading Room, which contains a special collection on Christian-Jewish Relations and the Holocaust.

Father Leavitt called it very significant that much of the money he helped raise was donated after the scandals of the clergy sexual abuse crisis.

“It showed me how deep the faith of lay people is and could be in the priesthood and in institutions like St. Mary’s,” he said.

While he thought the negative publicity would hurt morale among seminarians, Father Leavitt said today’s seminarians are the best group of men he’s ever seen. While there have always been individual good and holy men at the seminary, Father Leavitt said today there is a much more of a “group” pursuit of virtue.

“The seminarians come with a thirst for holiness and a thirst for character like I haven’t seen before,” he said.

Father Leavitt acknowledged that a lot of people had begun to wonder whether the priesthood had become “soft.”

“They wondered if these really are people that can live an ascetical life and live a disciplined life and live a richly human life without being married and without compensating in ways that are sinful or criminal,” Father Leavitt said. “These guys we have today give me confidence that they’re saying we can do that and we will do that because they love Christ and the church and the people so much.”

Father Leavitt said the priesthood is “no place for a weak person to hide any more or a person who’s trying to avoid growing up and facing the truth about himself or about this vocation.”

Formation at St. Mary’s had always been intellectually rigorous, according to Father Leavitt. But today’s seminarians receive pastoral formation that is vastly improved from earlier decades.

“These guys are so superior to what I was like back then,” he said. “We were just like altar boys with a lot of theological ideas. We didn’t know how to work with people in parishes.”

Father Leavitt recalled that in his first year at St. Mary’s, he was asked to visit patients who were psychotic and catatonic at a mental hospital.

“There was no training about psychosis and catatonia,” he said. “You just sat with them. How that added up to anything, I don’t know.”

Today’s seminarians have field training in parishes and other institutions in additional to their classroom training. They are encouraged to develop a pastor’s consciousness, Father Leavitt said.

There are still a lot of challenges. Smaller numbers of seminarians mean increased competition among seminaries, Father Leavitt said.

But as the Vatican considers the candidate nominated to succeed him, Father Leavitt said he is enormously optimistic about the future of St. Mary’s and the future of the priesthood.

“The priests that come out of St. Mary’s are intelligent and strong and good,” said Father Leavitt, who will take a one-year sabbatical during which he will return to academic writing. He hopes to come back to St. Mary’s as a professor.

“Our guys are incredibly impressive,” he said. “They just make me very, very proud.”

Cardinal William H. Keeler and Archbishop William D. Borders heaped praise on the longtime president-rector.

Archbishop Borders called Father Leavitt “a dedicated scholar” with outstanding experience and a strong vision, while Cardinal Keeler said Father Leavitt “served with great distinction,” becoming “synonymous with St. Mary’s in the minds of many of us.”

St. Mary’s board of trustees honored Father Leavitt with an evening celebration at the seminary April 28 that included tributes from current seminarians.