NEW YORK – At first blush, the scene seemed typical. In one of Manhattan’s trendiest neighborhoods, models strutted down the aisle amid flashing bulbs, pulsating music and a Chardonnay-sipping crowd. The designer promoting this fashion line was clad in New York-requisite black.

But his collar was square and white.

Father Andrew O’Connor is a Catholic priest. His new organic clothing line, Goods of Conscience, promotes the church’s social teachings by providing healthy labor opportunities for poor workers in Guatemala and the East Bronx section of New York.

Hand-woven, technicolor and ruggedly formal, Father O’Connor’s sartorial creations are made from naturally grown cotton. He uses raw dyes such as yellow wood and black walnut.

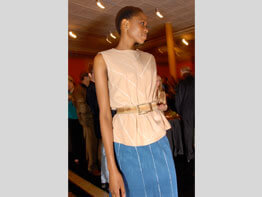

“It’s really great fabric,” said model Camilla Barungi, a finalist in the third season of the hit cable TV series “Project Runway,” as she showed off her full-length indigo skirt and short-sleeved beige top with three-button detail in back.

“It may not be silk charmeuse,” she added, but the eco-friendly style “is the future of clothes.”

Father O’Connor sells the garments from his Bronx workshop by appointment, and customers can preview them on his Web site, https://goodsofconscience.org. They aren’t cheap; shirts are priced in the $300 range, and a silk-batted ski jacket goes for $1,200.

“The construction of the cloth is superb,” said David Rose, owner and chief designer of the wholesale clothing company Ascari. And unlike other fancy duds, these products come packaged with a heartwarming story.

It starts in the southwestern mountains of Guatemala, in the small Mayan village of Chicacao, where members of the Tzutujil tribe live with no electricity. While on retreat there in 2005, Father O’Connor discovered villagers were struggling to preserve an ancient practice of making cloth from local ingredients such as cornstarch, calcium and water from the nearby volcanic lake.

Moved by the craftsmanship that went into weaving – the material for one shirt takes up to 15 days to create – and disheartened by the villagers’ meager wages, Father O’Connor hatched a plan to pay the workers to ship some of the fabric to New York.

Here the story turns to another poor community – this one near Father O’Connor’s Holy Family Church, yards from the Cross Bronx Expressway. Using a vacant convent attached to the church, where he is assistant pastor, the priest began employing immigrant seamstresses to make clothes based on his designs. Soon, with the help of $40,000 in donations, including one from filmmaker Michael Moore, the Goods of Conscience brand was born.

The clothes “look good, feel good and do good,” said Father O’Connor, 45, noting that money shipped back to Guatemala has already helped build portions of a church, school and roadway. “It’s a clothing line with a mission.”

On a recent day in Father O’Connor’s workshop, the air conditioner was on, and children scampered about. Dominican-born Maria Rivas, who earns $14 an hour, said she appreciates the shorter hours and laid-back atmosphere compared with her last sewing job, where talking was taboo.

“It was dehumanizing before,” she said through a translator. “Now it’s joyful.”

Father O’Connor said wearers of his clothes become part of a “cultural narrative” by helping preserve an indigenous Mayan craft threatened by mass-produced imports.

“The fabric the Indians make tells the story of their lives,” he said. “And they feel that Americans who wear their clothes truly understand who they are.”

“It’s a win-win, win-win-win situation,” said the Ascari company’s Mr. Rose.

To eliminate the threat of someone counterfeiting his clothing, Father O’Connor instructs the Mayans to thread a reflective fiber, similar to Scotch-Brite, into the fabric in crosslike shapes. (He won’t say where the fiber is from.) Made from tiny bits of glass, the fiber sparkles in the dark. The priest says his clothes are popular in New York nightclubs for this reason.

To Catholics and other Christians, the clothes, with their reflective crosses, have a spiritual feel. But they’re not made just for religious people. “I looked at the clothes and saw clothes. I didn’t see any religion behind it,” said Bree Braisile, 27, a fashion-conscious dancer who doesn’t attend church.

Born the fifth of nine children to parents of modest means, Father O’Connor has published poetry and studied Irish literature; he rides a Vespa. He began his art career as a painter in his early 20s, a decade before being ordained, and continues to work with bronze, multimedia tools and now clothing.

Some Catholics have scoffed at his unconventionality, and Father O’Connor himself acknowledged that Cardinal Edward M. Egan of New York worried at one point that his artwork might distract him from parish responsibilities.

But Father O’Connor argues that his clothing line carries with it an important social responsibility, noting that he based it on four pillars of Catholic social teaching: protection of one’s identity; preservation of the common good, including the earth; solidarity with the poor; and promotion of human dignity.

Meantime, his clients are pleased. “At least once or twice a day, a stranger will come up to me, touch the fabric and say, ‘I have to know where you bought that,’“ said Matt Spahn, 38, who arrived at the Manhattan fashion show in a fully lined, black military-style jacket from the Goods of Conscience line.