WASHINGTON – According to a recent FBI report, religious groups are not exempt from being targets of hatred.

The FBI’s report on hate crime statistics for 2008, released in late November, showed that the majority of hate crimes in the U.S. were motivated by racial bias but that religious groups and homosexuals were the next largest targets.

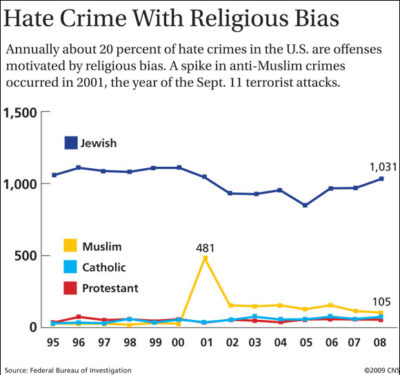

The overall number of reported hate crimes – more than 7,700 – increased about 2 percent in 2008. Although racially motivated hate crimes – the largest category – decreased by less than 1 percent, crimes against religious groups increased by 9 percent and crimes based on sexual orientation increased 11 percent over the previous year.

Hate crimes include acts of vandalism or property damage, intimidation or physical attacks. The FBI downplays year-to-year comparisons of hate crimes compiled since 1992, saying the increased figures could simply be the result of more local agencies tracking crimes. Civil and human rights groups say the figures are not accurate enough because not all hate crimes are reported.

Thomas Perez, head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, told reporters Dec. 17 that he was committed to putting a stop to violence stemming from hatred and bias and planned to hire 100 additional staffers to assist with the expanded federal hate crime laws.

In documented crimes against religious groups in 2008, Jews were targeted the most – 66 percent – while Muslims accounted for 13 percent and Catholics were victims of 5 percent of hate crimes.

The Anti-Defamation League said the new figures show a need for a national initiative to combat hate crimes.

Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, told USA Today that attacks on Catholics could be motivated by the church’s opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage. As Catholics become more vocal on issues, he said, they become targets for those who disagree with them.

The sense of a growing anti-Catholic sentiment was the focus of an Oct. 29 blog entry by New York Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan. The entry was an expanded version of an op-ed he submitted to The New York Times that was not published.

In the entry, the archbishop likened anti-Catholicism to “a national pastime,” citing frequent examples of anti-Catholic bias in the pages of The New York Times. He also said the bias was prevalent in the “so-called entertainment media.”

Laurie Goodstein, one of the reporters singled out in the archbishop’s blog, responded by saying she was disturbed to read his characterization that her work and that of her colleagues was anti-Catholic.

“You write as though the Catholic Church is some sort of special target, when in fact any institution that is accused of wrongdoing receives critical coverage and commentary,” she said.

Anti-Catholic bias, perceived or real, is hardly new. Several years ago in a column for America magazine, Jesuit Father James Martin, the magazine’s culture editor, noted that “examples of anti-Catholicism in the United States are surprisingly easy to find.”

He cited multiple examples in entertainment and advertising and placed the bias in a broader perspective, saying: “Anti-Catholicism in the United States is simply not the scourge it once was, nor is it today as virulent as anti-Semitism, homophobia or racism.”

Some say the increase of prejudice and hate crimes toward specific groups has been fueled by the economic downturn and the often polarizing discourse in American society.

The FBI’s report on hate crimes was released just weeks after President Barack Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expands federal hate crimes legislation to include crimes committed because of the victim’s gender, gender identity or sexual orientation.

Previously, the federal hate crimes law only protected those attacked on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin. An expansion of the law was initially introduced in 2001 and had been reintroduced every year since.

The expanded legislation was named after two men killed in separate hate crimes. Shepard, 21, died in October 1988 after being beaten by two men in Laramie, Wyo., because he was gay. Byrd, a 49-year-old African-American man, was killed in June 1998 by three men in Texas who dragged him behind their pickup truck.

On the subject of expanding federal hate crimes laws, religious groups were divided.

Some vocalized their support, stressing that religious principles demand equal protection of all people while other groups expressed concern that the measure would threaten their constitutional right to speak out on moral issues.

Some religious leaders questioned the possibility of being prosecuted if someone committed a hate crime because of a sermon or pastoral counseling labeling homosexuality as immoral, but constitutional specialists have dispelled this concern, stressing the free speech protection of the First Amendment.

Although Catholic Church officials did not take a stand on the issue, a Catholic priest defended the legislation during a Capitol Hill rally in 2007 when the legislation was reintroduced to Congress.

Dominican Father Charles Bouchard, past president of Aquinas Institute of Theology in St. Louis, said attempts to expand the legislation were not meant to “create special rights” or “endorse any lifestyle.”

Instead, he said the expanded hate crimes legislation was a means to “simply offer appropriate legal protection for persons who are victims of violence because of who they are and ensure that workers are judged on the basis of their job performance and not the basis of prejudice.”