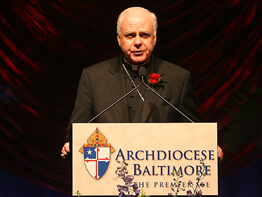

VATICAN CITY – Military chaplains must be voices of conscience and defenders of the human rights of their own soldiers, enemy combatants and civilians, said Archbishop Edwin F. O’Brien of Baltimore, who headed the U.S. Archdiocese for the Military Services for 10 years.

Where there is an acceptance of the direct killing of noncombatants or where torture is justified to obtain information, the chaplain service is either absent or not doing its job, the archbishop told a Vatican-sponsored course for military ordinaries and chaplains.

“The vicious and utterly barbaric treatment of individuals” in the U.S.-run Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq “leaves no doubt as to the barbaric extremes to which human beings can resort, especially in times of war,” the archbishop told course participants Oct. 13.

“It is significant, perhaps, that this prison did not have an assigned chaplain, though Army regulations required one,” he said.

The course, focusing on cooperation among religions to promote humanitarian law and human rights in situations of conflict, was sponsored by the Congregation for Bishops and the pontifical councils for Justice and Peace, for Interreligious Dialogue and for Promoting Christian Unity.

Archbishop O’Brien told course participants that the “obligation of the international military communities to take seriously and to respect” the religious beliefs of others is “critical today” given the increase of multinational peacekeeping forces and ongoing tensions in the Middle East.

All chaplains, he said, must have a solid training in their own religious tradition, but also knowledge of and respect for the faith of others.

“Knowledge and respect for others’ religious beliefs must even extend to providing them with otherwise unavailable resources for prayer and worship,” he said. “Islamic prisoners of war, for example, should whenever feasible be given a prayer rug and a Quran.” The Quran is the sacred book of Islam.

Given the denominational and religious mix found in situations where chaplains work, the archbishop said, they must be educated “in an across-the-board acceptance of basic principles: respect without proselytizing; a basic understanding of other faith groups’ beliefs, customs and disciplines; the role of the chaplain not as warrior but as peacemaker and bridge builder; objective evaluations of chaplains’ performance leading to promotions in rank without regard to denomination.”

A chaplain’s task is to be the voice of the lowest-ranking soldiers and the victims of war, he said.

“He must be the voice of conscience, not intimidated by rank or power in speaking out,” Archbishop O’Brien said.

“Where there is an acceptance of direct killing of noncombatant civilians, for instance, there is no chaplaincy worth its name. Where torture is justified in eliciting prisoner information, chaplaincy is ineffective or nonexistent,” he said.

Chaplains are expected to intervene to stop torture, he said, as well as to help the military command determine what methods of questioning are appropriate and what methods cross the line into torture.

“Regardless of rank or power or position, the chaplain must see himself primarily as a man of God and not as an agent of the state,” said the archbishop. “To put it another way: He must wear his uniform and rank on his body and not on his soul.”

Archbishop O’Brien said that if, outside the confines of sacramental confession, a chaplain discovers evidence that international humanitarian laws are being violated, he has an obligation to report the incident “to the appropriate authority with as much discretion as possible.”

The archbishop said the chaplain’s role as a voice of conscience obviously extends to his interaction with individual soldiers, many of whom are young and have never faced the “implicit contradiction” between the commandment not to kill and the real possibility of being forced to shoot someone in self-defense or to protect others.

If a soldier comes to the decision that “bearing arms is an un-Christian act for him,” the chaplain must offer his support, the archbishop said.

Archbishop O’Brien called for “ecumenical and interfaith” cooperation in educating chaplains in humanitarian law and in promoting the protection of human dignity by all members of every nation’s military services.