- Contact Us

- Careers

- Policies

- About Us

- Events

- Parishes

- Schools

- Ministries

- The Office of Black Catholic Ministries

- Hispanic Ministry

- Charismatic Renewal

- Marriage & Family Life

- College Campus Ministry

- Miscarriage Ministry

- Prayer Ministry

- Deaf Ministry

- Prison Ministry

- Disabilities Ministry

- Divine Worship

- Divorce Support

- Faith Formation

- Grief Ministry

- Mental Wellness Resources

- Respect Life

- Seek the City to Come

- Young Adult Ministry

- Youth Ministry

- LGBT Pastoral Accompaniment

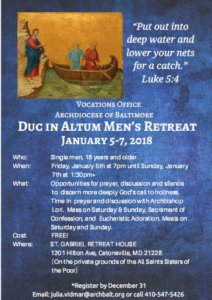

- Vocations

- myArch

- Outlook365

- Ethics Hotline

- Giving

- Promise to Protect