The Least of These: Church helps fight opioid addiction

Second in a series

Editor’s Note: Inspired by Matthew 25:40-45, which concludes ” … what you did not do for one of these least ones, you did not do for me,” each month in 2017 the Review will provide an in-depth look at the Catholic Church’s response to those in dire need.

By Paul McMullen and Erik Zygmont

That heroin deaths have surpassed gun homicides, according to 2015 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is just one piece of evidence of the growing epidemic of opioid abuse.

According to a 2015 report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, every day in our nation more than 650,000 prescriptions for opioids, which act on the nervous system to relieve pain, are dispensed – and 580 people initiate use of heroin, an illicit opioid.

Unlike alcohol, drugs on the black market are not accompanied with warning labels or information. Many are spiked with substances such as fentanyl, an unusually potent opioid.

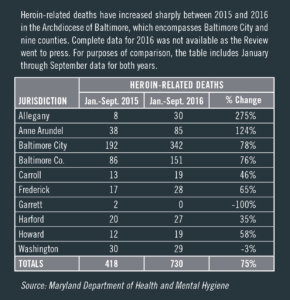

The number of statewide heroin-related deaths more than tripled between 2010 and 2015, from 238 to 748. Last year was even more deadly, with 918 fatal overdoses through September.

The opioid epidemic does not discriminate, ravaging the city and suburbs. It has hurt local economies, school systems, the health care system and the home.

In the second installment of its “Least of These” series, the Catholic Review shares how a rehabilitative housing program for women in Baltimore City founded by two religious orders and the substance abuse ministry at a parish in Harford County offer support during the crisis.

Doing the work

“Addiction is a powerful thing,” said Joy Haywood, who went on to add, “To be loved is the best high in the world.”

Haywood, 57, speaks from experience. Addicted to alcohol and heroin since the 1980s, her life turned for the better in 2014, when she entered Marian House, a rehabilitative housing program for homeless women and their children based in Baltimore’s Waverly neighborhood.

Haywood aspires to mark three years since her last use of a controlled dangerous substance on Feb. 4.

Marian House, meanwhile, will celebrate its 35th anniversary in April. Co-founded by the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the Religious Sisters of Mercy, its original mission was to support women released from jail; its legacy includes helping more than 1,500.

In fiscal year 2016, 94 percent (67 of 71) of the women served by its transitional housing program arrived with a chemical addiction. For FYs 2011, 2012 and 2013, every woman who entered Marian House had an issue with substance abuse. However, 97 percent of alumnae in that cohort reported no drug or alcohol abuse within the past month and had an average sobriety of 60 months.

The typical woman spends nine months to one year at Marian House I, based on Gorsuch Avenue, on the campus of the former St. Bernard Parish and School. The “intensive rehabilitation phase” of its program includes housing, meals, individual and group therapy, pre-GED and GED education, referrals for medical care – and treatment and counseling for addiction.

“Our model is unique,” said Katie Allston, executive director since 2007 and the nonprofit’s first lay leader. “We don’t charge women a dime.”

Haywood gave witness to that comprehensive approach while sitting in her north Baltimore apartment on a day off from her job as a custodian at the National Aquarium, where she has worked since October 2015.

She described growing up in a loving home. Upon graduation from Baltimore’s Walbrook High School, Haywood entered the U.S. Army Reserves and hoped to follow her mother into the nursing profession, but in civilian life began “hanging with the wrong people.”

“My self-esteem was non-existent, I was too conscious and aware of myself, too judgmental,” Haywood said. “Drugs and alcohol became an escape.”

She used while holding down factory jobs, as a security guard and even as a correctional officer, where co-workers “became my getting-high partners.”

Haywood bought on the east side, ashamed that her mother, who lived on the west side until her death in 2005, “would see me.” Her addictions grew, along with her arrest record. Family enabled her, but it was to give Haywood money to feed her habits so that she did not have to prostitute herself.

During a 21-day stay at a treatment center, this one in Taneytown, a counselor directed her to Marian House.

“Every woman who comes here tells me a story,” Allston said. “It typically begins with a childhood trauma, a death in the family or neglect. Even something as simple as a car accident can lead to an early addiction to pain medication.”

Haywood warned Allston, “I don’t trust many people,” but from the CEO to house manager Sharon Kennedy, and from director of operations Peter McIver to School Sister of Notre Dame Jane Forni, one of her case managers, she was not let down.

“All that I knew was what to do to get high,” Haywood said. “What would these wonderful people want with someone like me? Once I got there, it’s not like you’re only going to one person for help. Everyone there knows me, loves me.”

Haywood returns often, to say hello and visit with Vonsetta Manns, a clinical social worker.

“She knows everything about me,” said Haywood, a self-described introvert. “It was more than us talking. My teeth were bad, but she got me to the University of Maryland (dental school) for care. She helped me find balance, not just to be Joy, but the best Joy I can be.”

Faith is part of that recovery.

“Among the women in the program, there is a lot of guilt involved,” Allston said. “We try to help them see the love of God. They think they’ve lost God. We know they haven’t.

“Being here is not easy. Joy worked hard, and made the choice to do so. That’s what our women do. They do the work.”

Haywood said she has regular talks with her maker.

“I’m grateful for the blessing called recovery,” she said. “I know that Katie is going to say, ‘Good job,’ but it’s all by the grace of God.”

Strength in numbers

Jim Kurtz wants to plaster the state with billboards asking “Do you know where your teaspoons are?”

A self-described “IT guy,” he does most of his work from his Bel Air home. He and his wife, Helen, usually had a handle on the whereabouts of their live-in, mid-20s daughter, Caroline; it was the ever-lightening silverware drawer that baffled them.

“All the teaspoons were missing, and we couldn’t figure out why,” Jim said.

In January 2015, Helen was cleaning her daughter’s room when she spied her old middle school backpack. The upper portion was stuffed with candy; under that were the missing spoons and the most sinister paraphernalia a parent could imagine – needles, cotton swabs, little pieces of folded paper.

“We had been dancing around it for three years,” Jim said. “We didn’t know what we were dancing around, but this proved it was heroin. This proved it was the big-time, can’t-get-any-worse-than-that stuff.”

For two years now, the Kurtzes have been staring the truth in the face: “This is now your life. Your son or daughter is a drug addict, and that’s it.”

“It overshadows everything,” Helen observed, including the birth of their older son’s first child.

They had help facing up to the truth.

After “traveling around” to several groups and organizations created to help the addicted, their loved ones or both, the Kurtzes, parishioners of St. Ignatius in Hickory, settled on Families Anonymous, part of the robust Substance Abuse Ministry at St. Margaret Parish in Bel Air. The organization bills itself on its website, familiesanonymous.org, as a “12 Step fellowship for families and friends who have known a feeling of desperation concerning the destructive behavior of someone very near to them, whether caused by drugs, alcohol or related behavioral problems.”

“What we have learned at Families Anonymous is to share,” Helen said. “Tell your family; tell the people you work with.”

In 2015, Jim took the advice whole hog, wiring his famous set-to-music “Kurtz Christmas Lights” to include a dedication of Rachel Platten’s now ubiquitous “Fight Song” to his daughter “and to everyone in Bel Air, Maryland; Delray Beach, Florida; Lemont, Illinois; and Moscow, Pennsylvania who fight every day to take back their lives.”

“We ask that you pray for them and for their long-term recovery,” intones a light-up image of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

The spectacle may be found on YouTube.

On its website, FamiliesAnonymous.org is described as a “12-Step fellowship for families and friends who have known a feeling of desperation concerning the destructive behavior of someone very near to them, whether caused by drugs, alcohol or related behavioral problems.”

On its website, FamiliesAnonymous.org is described as a “12-Step fellowship for families and friends who have known a feeling of desperation concerning the destructive behavior of someone very near to them, whether caused by drugs, alcohol or related behavioral problems.”

“What we have learned at Families Anonymous is to share,” Helen said. “Tell your family; tell the people you work with.”

St. Margaret parishioner Larry Signorelli launched Families Anonymous at the parish in 2010 to honor the memory of a counselor who helped his family during the early stages of his own daughter’s addiction.

“I get help by helping others,” said Signorelli, who estimates that the ministry has assisted about 125 families.

Rather than a sharing of stories without comment, the Alcoholics Anonymous model, Families Anonymous includes a lot of “cross talk” – exchanges of ideas, commiseration and shared hopes.

Helen said that the first time she attended a Monday night meeting, “I could hardly breathe,” let alone talk.

Now she – who had called it “just a phase when her daughter had experimented with alcohol and marijuana in high school – speaks plainly.

“I’m always glad I went, because it has helped me or I have helped somebody, even if all I’ve said all night is ‘You had better lock up your jewelry,’ ” Helen said.

There’s a levity to the harsh words as she and Jim speak of their struggle. Of the worst news a parent could receive, Helen said, “We’re always waiting for that other shoe to drop, but we’re not holding our breath anymore.”

Jim displayed a talking naloxone injector, which delivers instructions for administering the anti-overdose drug. (The Harford County Department of Public Health has trained public school nurses to administer the drug.)

For now, Caroline is in a recovery facility in Pennsylvania.

Jim and Helen are realistic but hopeful. They give their daughter daily conversation, unconditional love, support and prayers, but – on the advice of a counselor – next to nothing material outside of Jim’s health insurance.

“She has more respect for us now because she doesn’t see us as wimps and saps anymore,” Helen said. “She can’t manipulate us anymore.”

They are helping their daughter find her ability to stand on her own, and were recently impressed when she finagled a spot in a sober house that accepted Jim’s health insurance, a rarity.

“She’s resourceful,” Helen said with a wry smile.

Breaking Heroin’s Grip

Maryland Public Television will air the documentary “Breaking Heroin’s Grip: Road to Recovery” and provide phone bank help on all its stations Feb. 11, at 7 p.m. For more information, visit breakingheroin.com.

Also see:

The Least of These: As weather turns, Davidsonville parishioners open doors, hearts

Vigil remembers overdose victims in Westminster

‘We had to do something’: Westminster parish launches 12-step program after parishioner overdoses

With incarceration, homelessness in rearview, Baltimore man navigates road to self-reliance

SaveSave